In Canudos, a backlands town in the Northeastern State of Bahia, Antônio Conselheiro (Anthony the Counselor) preached against the republic. His followers, leather-clad ruffians or ‘jagungos’, terrorised the countryside. In the 1890s the Republic of Brazil was in its infancy and insecure, rumours of monarchist plots abounded, troublemakers like the Counselor needed to be dealt with. He had gathered a large following, apparently for his indifference to suffering rather than his skill as a preacher.

“His had been a harsh schooling indeed, in hunger, thirst, bodily weariness, repressed anguish and deep-seated misery. There were no tortures unknown to him. His withered epidermis was wrinkled as an old broken and trampled breastplate over his lifeless flesh. Pain itself had come to be his anaesthetic; he bruised and macerated that flesh with hairshirts more cruel than any matweed; he dragged it over the stones of the road; he scorched it in the embers of the drought; he exposed it to the rigors of the cold night dew; in his brief moments of repose he put it to bed on the lacerating couch of the caatingas.”

Soldiers carrying modern rifles bore down on the five thousand or so mud huts that made up Canudos. The jagungos armed with blunderbusses or ‘trabucos’ were completely outgunned and outnumbered. However, the Brazilain army was embarrassed, their expeditions from the coast were badly supplied and the march to Canudos was treacherous; their enemy was brave and resilient:

“The truth is, frugal and parsimonious in the extreme, these rude fighting men who in a time of peace would go through the day with two or three handfuls of passoca and a drink of water, had in a time of war made abstinence a matter of discipline and had carried it to so high a point that they were capable of an extraordinary degree of physical endurance.”

The army was bamboozled as the enemy employed hit and run tactics, using the terrain to their advantage. A handful of guerillas hammering a conventional army was a story to be echoed in Vietnam, Algeria and Cuba. The army had Kruger artillery guns, labouriously dragged to the field of battle, they fired grenades but initially didn’t bring much of an advantage. The army’s most effective troops were the mounted ‘vaquieros’ from the south: gaucho cowboys who could at least round up some cattle for the starving soldiers, and there was a battalion of police who themselves were backlanders and could play the jagungos at their own game of hit and run.

The Canudos campaign happened in 1897 two years before the Boer War started. I’ve heard the British-Afrikaner conflict named the first to feature guerilla tactics, apparently not, and I doubt Canudos was the first either. Hundreds of wounded government soldiers wandering through the backlands on their return to civilisation became a scourge:

“The country along the roadside, which up to then had been populated, was now turned into a waste land, as these tumultuous bands stormed through it, leaving destruction in their wake, like the remnants of some caravan of limping savages.”

Da Cunha spends Part One of the book detailing the geology, flora and fauna of the backlands and also the racial make-up of its human inhabitants. The summary is that ‘os sertões’ (the backlands, literally drylands) are plagued by drought, treacherous terrain and prickly bushlands or ‘caatingas’, which tore through the soldiers’ uniforms, but not the jagungos leather. The people, largely isolated from the coast for three hundred years, were of a particular racial mix and culture, in the main they were Caboclos (mixed white and Indians), there were also Cafuzos (mixed black and Indian), and Mulatos (mixed black and white). Da Cunha, who I think was of mixed race himself, calls these mestizos inferior. You have to remember social Darwinist theories were popular at the time. Apparently, the only pretty women in the backlands were of the “Jewish type”. As the narrative progresses Da Cunha changes his tune and recognises the resilience and resourcefulness of the sertanejos (backlanders). Part one of the book was unnecessary for me, as the author later describes the landscape so well in his battle narrative:

“Meanwhile, it was known that this road ran through long stretches of caatingas, necessitating the use of the pick in clearing a path; and it was further known, that a march of twenty-five miles in this midsummer season was out of the question unless each man carried a supply of water on his back, in the manner of the Roman legions in Tunisia.”

The writing is dense and the conflict in Canudos was a never ending string of muck-ups by the Brazilian army. Aware of course that the real problem came from the lack of strategy from the commanders, Da Cunha also explains the weaknesses of the common soldiers:

“In battle, to be sure, the Brazilian soldier is incapable of imitating the Prussian, by going in and coming out with a pedometer on his boot. He is disorderly, tumultuous, rowdy, a terrible but heroic blackguard, attacking the enemy whether by bullet or sword thrust with an ironic jest on his lips.”

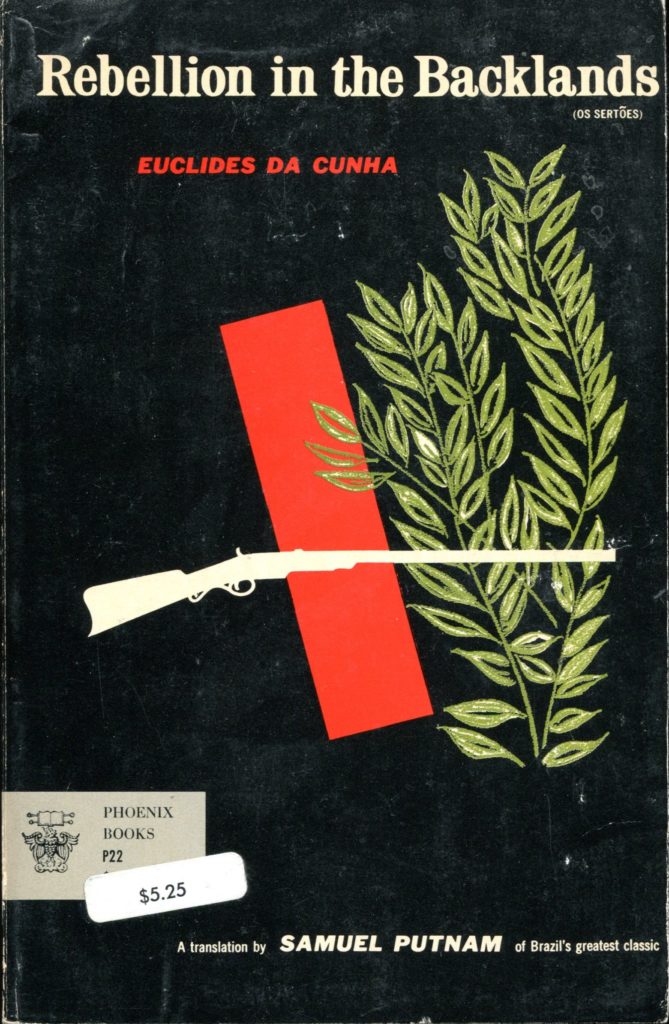

Rebellion in the Backlands is a classic, it reminded me of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence because of the beautiful descriptions of a desert landscape. I also found there was a lot to wade through in between the odd passage in which Da Cunha’s prose (through translation) really shines. With the historical references and amount of detail, pathos and analysis here, Da Cunha was evidently an incredibly knowledgeable individual, he died in a gunfight with his wife’s lover at age forty-three. An unfaithful wife was something he shared with Anthony the Counselor, for whom such a betrayal led to fifteen years wandering the backlands, and his subsequent elevation to mesianic status.