Originally published in the Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel as When Malaparte Met Mao.

A former fascist sees only the good in Mao’s China.

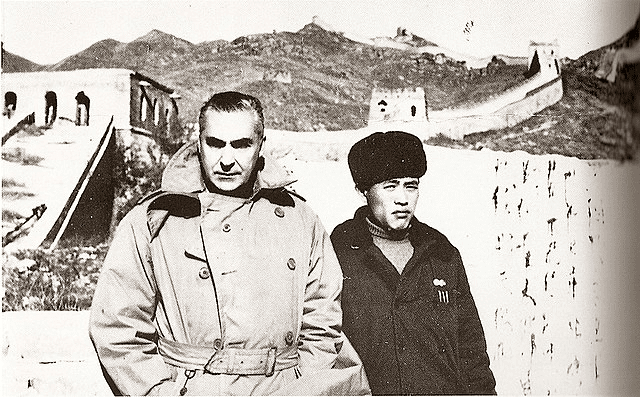

In 1956 Italian novelist Curzio Malaparte received an invitation to travel to Beijing for a commemoration of the death of writer Lu Xun. Malaparte is most famous for his quasi-surrealist WWII novels, ‘Kaputt’ and ‘La pelle’ (The Skin).

In Kaputt, as a journalist and officer in the Italian army, he narrates happenings from behind the Eastern Front. Episodes from the Ukraine, Finland, Romania and Poland, get us up close and personal with, amongst others, members of the Nazi elite. Malaparte seems to revel in the horrific subject matter, showing the abuses and hypocrisies of the Axis forces like no other.

In The Skin he is a liaison officer attached to the American army, taking us on a Dantesque tour of the hell that is Naples after Allied liberation. He exposes the naivety of the Americans and the damage done to the already miserable local population.

Malaparte was a keen observer, who did not shy away from making criticisms, why then on his trip to China was he so charmed by everything? Did he leave his critical faculties back in Europe? If so, he is hardly alone, many a fierce social critic from the West has found utopia far away from home. Did these utopias exist? Or were they merely projections of deep spiritual and humanistic urges? Malaparte’s trip to China was recorded in his book ‘Io, in Russia e in Cina’ (Me, in Russia and in China). The book was published posthumously – so the author didn’t come up with the solipsistic title. While the book includes interesting anecdotes from Stockholm, Moscow, Siberia and Ulan Bator – the bulk of it is made up of articles and notes about China.

Malaparte meets with a Chairman Mao happy to receive him, as in 1956, friends from the West are rare. Malaparte, apart from commenting on the chairman’s obsidian black teeth, is nothing but complimentary about Mao, his vision for China, and his role in achieving it. He falls for the cult of personality, just like he did with Mussolini in his pro-fascist youth. He writes of Mao that:

“Above all, his gaze fascinated me; serene, sweet, deeply kind.” (Me, in Russia and in China, henceforth ‘R and C’)1

In the interview, Mao asks about the state of things in Italy and they compare prices and salaries between their two countries. Mao welcomes any criticism the visitor might have of China. Malaparte’s only issue is that he wants those imprisoned for their Christian faith released. Interesting that Mao ‘welcomed’ a critique here because The Hundred Flowers Movement had already begun. The idea of this movement was that Mao encouraged criticism of his regime as a clever way of exposing his political enemies. Malaparte says his meeting was in private and lasted nearly an hour – both claims are unlikely, but certainly the interview took place.

By 1956 the Soviet Union had faded as a utopia for alienated Western intellectuals while China still showed hope of being socialist heaven. Khrushchev had denounced the wrongs of Stalin, but in China, the Great Leap Forward, invasion of Tibet and Cultural Revolution were yet to come.

In February of 1956, Hungary had rebelled against its Soviet masters and been cruelly crushed. Much of the discontent in Hungary had been caused by policies that Mao was about to implement, for example, unrealistic production targets – which lead to the falsification of industrial output figures. The upshot of these bogus numbers was a scarcity of goods and inflation. Hungary also had the extra burden of paying war reparations to the Soviet Union. Among those who fled Hungary in the aftermath of the 1956 revolution was one Paul Hollander, who later wrote a book tackling the problem of Western intellectuals enamoured of the Soviet Union, China and Cuba. His book ‘Political Pilgrims’, published in 1981, will help in analysing Malaparte’s uncomfortably glowing report on China.

In 1915 Malaparte ran away from home in Tuscany as a sixteen-year-old to fight in France against the Germans. There, in 1918, his lungs were damaged by gas – nearly forty years later his weakened lungs would strike him down while on his reverie in China. His father was German and his mother was Italian. He was a fan of Mussolini at first but later critical of Il Duce (and Hitler) and put in jail for it. Malaparte claims he served five years but his influential friend, Mussolini’s son in law, got him out earlier. As a man, his gift was art, not the truth, not moral consistency, nor politics. As with many brilliant intellectuals, he didn’t feel that he got the kind of attention he deserved. After the Second World War, he was often maligned for his fascist past. A stint in Paris in the late 1940s came to an end as he was not as popular in literary circles as he’d once been – he returned to Italy and turned towards the Italian Communist Party.

Hollander puts to us some theories to explain why Western intellectuals become disillusioned with their own societies and look towards authoritarian socialist states for meaning. First, the very freedom of Western news media and its sensational critiques of society encourages a negative viewpoint. Also, formally religious teachers and the keepers of meaning, intellectuals now (or since the late 19th century) no longer have a clear role in the secular society. With no paradise in the next world to look forward to, it must be found (or founded) in this life. Foreign dictators can be attractive to intellectuals as philosopher kings, a perfect combination of the man of action and intellectual. Malaparte tells us of Mao:

“If his prodigious life as a man of action and as a revolutionary is the mirror of his courage, of his spirit of sacrifice, of his iron will, his face is the reflection of his good, generous soul. When you think about what the Chinese revolution might have been if at the front of it there had been a fanatic, a bloodthirsty, a lucid, abstract, ruthless theorist, one shudders. “(R and C)

With hindsight the irony of the above passage makes us shudder. Socialism has obvious appeal – the participation of all citizens in the building of a fair and equal society. Noble aims do not excuse the wrongs done in the Soviet Union, Hungary, China, Cuba etc, however. (Much like the stated aim of protecting freedom does not excuse the crimes of the United States in Vietnam or Iraq.) Reviewing his time in China Malaparte does not agree:

“I also suffered when reading the Budapest news in the press, but this suffering never raised doubts. The great and positive Chinese experience absolves any error, since it demonstrates undeniably that the sum of the positive factors in the balance of progress is always superior to that of errors.” (R and C)

Many intellectuals visiting socialist states missed or ignored things we now know about like show trials and famines. Part of this was because they didn’t want to give up their dream of socialist utopia, another factor is what Hollander calls the techniques of hospitality. These people were welcomed and guided – made to feel important by having access to leaders and academics, they were given good food and accommodation and most importantly saw only what the government wanted them to. Belgian sinologist In the 1970s, China watcher, Simon Leys noted with disdain that Western visitors kept on running into each other in China – because their hosts reduced China’s near infinity to just a dozen villages to visit, and around sixty vetted individuals to meet. Flattery was also part of the techniques of hospitality. Writers and other artists were ‘accidentally on purpose’ put together with locals who knew and loved their work. China still uses this kind of tactic given the opportunity. When Trump (not strictly speaking an intellectual) visited in 2017 they put a real show on for him, treating him like an emperor – having a dinner party for him in the Forbidden City. It worked, Trump thought of President Xi was a swell guy, for a while at least. I wonder if Xi told him he enjoyed reading ‘The Art of the Deal’? Malaparte also fell victim to such flattery – he is touched by crowds of ‘spontaneous’ well-wishers when he falls ill in China.

Stalin used the famous writer Maxim Gorky to welcome foreign writers and make them feel important. In the 1930s Gorky met H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw and Andre Gide amongst others. With Gorky we have a local intellectual suspending his critical faculties to fit in with the regime. Gorky’s case is especially sad as he was once the chronicler of the downtrodden in Tsarist Russia. He was flattered by Stalin and made chairman of the Union of Soviet writers. The artist was no match for the manipulator and destroyer of men’s souls. From Gorky’s book ‘My Childhood’. I learned that his father died when he was young and his mother largely ignored him. No wonder in later years he craved attention and recognition – Stalin would have been well aware of this too.

In 1933 Gorky, at the bequest of Stalin and the secret police, arranged for a group of Soviet writers to visit the White Sea-Baltic Canal being constructed by gulag workers. The writers then collaborated on a book singing the praises of Stalin and his gulags that liberated the prisoners through labour – never mind that thousands of the canal workers died. Gorky could never bring himself to believe that these deaths happened. He himself died in suspicious circumstances. Incidentally, Gorky’s adopted son was with Malaparte in France fighting the Germans in WWI. In an anecdote (set I believe in the early 1930s) Malaparte gives us an insight into Gorky’s nature:

“Gorky… made a point of telling me that in the midst of the revolution there had been an elite of opportunists, a kind of new bourgeoisie whose only ambition was to enrich themselves and enjoy life. This was not news to me, everyone knew it and everyone knew not only what Gorky thought about it, but also what Stalin thought.” (R and C)

Malaparte wasn’t as controlled by his hosts as Hollander might have suspected. In one episode he walks around the city of Datong unaccompanied by his French-speaking translator, Hong Sing. Malaparte was smart enough to know Hong Sing was there to make sure he didn’t get the ‘wrong’ idea about anything. This comes to light when they visit a theatre show in Xian and Hong translates the satirical dialogue in reference to the regime’s labour policy. Realizing his mistake, Hong quickly restranslates:

“ And then we hear a few words of dialogue, like this: ‘We must work day and night to increase production’ (which in this case is a scientific production, as if scientific production could be increased by a simple order from above), and a young assistant replies: ‘But we do not work for production!’ To this, the audience laughs… Hong Sing, kindly concerned to avoid misunderstandings, and things being judged wrongly or unfavourably, insists on saying that the two lines translate as follows: ‘It’s necessary to work day and night, otherwise you work against production’, and ‘but no, we do not work against production’. It may be that the right translation is the second but the first translation is also from Hong Sing. And then, what would there be to laugh at in the second translation?” (R and C)

So Malaparte gets a whiff of undercurrents in Mao’s China but doesn’t pursue. Likely well aware of some of the problems, he toed the line as he was sending reports to the communist magazine Vie Nuove back in Italy. (He was also sending articles back to the more right-wing Tempo.) The then editor of Vie Nuove, Maria Antonietta Marocchi, was later heavily criticised on French TV by Simon Leys for her overly positive book about Mao’s Cultural Revolution, ‘Dalla Cina: dopo la rivoluzione culturale’ (From China: after the Cultural Revolution). In 1977 she was expelled from the Italian Communist Party for supporting Maoists in Bologna! In Political Pilgrims, Hollander includes quotes from her singing the praises of the Chinese for being well washed with soap and water and completely without makeup. She is an example, for Hollander, of an alienated person looking for virtue and purpose in China. Another anecdote Hollander records that is worth mentioning comes from the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, in the book ‘China! Inside the People’s Republic’, published in 1972. A committee member asks an old Chinese lady with cuts on her hands from removing slivers of metal from oily rags, whether it hurts. The lady replies in the negative – she is doing it for the revolution so it doesn’t hurt.

Hollander and Simon Leys had their sights firmly fixed on those, like Marocchi, who allowed themselves to be duped by Potemkin villages, essentially show villages (or hospitals or prisons etc.). In the late 18th century Russian Empress Catherine went on a tour of the Crimea, the New Russia taken off the Ottomans, to see her new subjects (who weren’t there yet!). Her advisor Potemkin arranged for his men to travel ahead of Catherine, erecting temporary villages to impress her. The technique has since been used many times, with many variations: in the Soviet Union with model work camps, in China with show fields teeming with rice during the Great Leap Forward – and, one might argue the entire city of modern Pyongyang is a Potemkin village.

Malaparte’s tour of China was quite extensive and so I find it hard to believe he only saw ‘Potemkin’ setups. In any case, the CCP did not become expert in providing these until later in the piece. After seeing a utopia of plentiful crops, industrial development and happy workers in Beijing, Lanzhou (of all places), Taiyuan, Urumqi and Xian – Chongqing throws a spanner in the works for Malaparte with its coolie labourers.

“The image, however, that man offers of himself, even in this verdant peace, in this serenity of nature, in this wealth of works, is the habitual image of man humiliated by misery, who struggles and suffers for his redemption. Thousands of men with sticks on their backs, bent under the weight of two baskets laden with stones, travel miles and miles, trotting, to carry stones to the lime kilns, which abound in the region of Chongqing. Here man is not degraded to the condition of a draft horse, but that of a beast of burden.”

So equality is yet to be established in The People’s Republic, but Malaparte sees the hope of a great socialist future in these workers’ eyes. He also suggests that the conditions in the city may be a hangover from the Kuomintang era. Maybe had he lived longer he could have written a novel about wartime Chongqing as brilliant as The Skin was about wartime Naples – and, as his biographer, Maurizio Serra points out, perhaps had he lived beyond 1957 he would have woken up to the enormous defects of Mao’s China.

“Considerations about Chongqing when it was capital of the Kuomintang and seat of Chiang Kai-shek…Prostitutes from Shanghai, Hong Kong. People in appalling misery and oppression. Drunken American soldiers offered grass to beast-of-burden-like workers. Popular song: ‘Laugh at poor people, but not at whores.’”

What was Malaparte capable of as a writer? Why am I unsatisfied with his rather shallow work on China? When I read his novel Kaputt, I felt like I had never come across a writer so compelled to explain the dark side of the human spirit to us. Sure Primo Levi’s account of his time in Auschwitz ‘Se questo è un uomo’ (If This Is a Man) is a masterpiece, but he was a victim, he can dismiss the Germans as merely evil. In Kaputt, Malaparte, although a lifelong anti-German, is compromised by being an officer in the Italian army and a former enthusiast of fascism. He knows what it’s like to be on the wrong side of history. WHAT is it like though? Why does evil happen? Answers must be found. He visits the Jewish ghettos of Warsaw, Krakow and other Polish cities, wishing to go alone, but always trailed by a Gestapo officer. He sees the ragged and starving, and bodies lying on the streets waiting to be loaded onto carts and be taken away. But there are not enough carts. He dines with the German Governor-General of Poland Hans Frank, the very man who is in charge of these ghettos. Malaparte wants to see inside Frank’s soul, to explain the evil to us:

The opinion I had formed of Frank long ago was, unquestionably, negative. I knew enough of him to detest him, but I felt honor bound not to stop there. Of all the elements that I was conscious of in Frank, some a result of the experience of others and some of my own, something, I could not say what, was lacking-something in his very nature of which was not known to me but which I expected would suddenly be revealed to me at any moment.

I hoped to catch a gesture, a word, an involuntary action that might reveal to me Frank’s real face, his inner face, that would suddenly break away from the dark, deep region of his mind where, I instinctively felt, the roots of his cruel intelligence and fine musical sensitiveness were anchored in a morbid and, in a certain sense, criminal subsoil of character. (Kaputt)2

I am in no way trying to compare China in the 1950s with Poland under the Germans (nor Naples under the Americans). In Malaparte’s analysis of Frank, we see a great critic of the powerful – he wrote similar insights about Mussolini and Lenin – why not Mao?

In a chapter in The Skin entitled ‘The Black Wind’, Malaparte, this time in Ukraine, is asked for help from men crucified at the side of the road. The help they want is to be shot not cut down. In the same chapter, he comes across a wounded American soldier in Naples and claims he cannot bear to see men suffering – that he would rather kill a man than see him suffer. Other horrors in Naples include mothers selling their children as prostitutes to Moroccan soldiers and a man-made into a pancake by falling under the tracks of a moving tank. From these examples we learn that Malaparte saw hell in his life, however, his empathy for the suffering never left him. Can we admire him for that? Can we blame him for trying to find a utopia in China shortly before his death in 1957 at the age of fifty-nine?

At the end of Me, in Russia and in China, Malaparte falls ill with pleurisy and one of his lungs collapses. He is confined to the hospital in Wuhan (yes Wuhan!) for a period of three months before he is able to make the arduous journey back to Italy in a Soviet plane. He praises the doctors who attend him and the conditions in the hospital – and claims that he received no special treatment – that all patients in China get such care. This seems doubtful, given his importance to the regime as a potential propaganda agent. Malaparte tells us that Hong Sing is very keen for him NOT to die in China and I can’t help thinking that the translator’s fate would not have been a good one if any misfortune had befallen his charge. (Dying of course being the ultimate mishap.)

Malaparte’s account of his time in China does have some redeeming features. Being well-read he can relate some of the landscapes he sees to poems by Du Fu and Li Bai. He appreciates Chinese sculpture and makes interesting comparisons to artworks in Venice. Like many a Westerner in China, he has some amusing anecdotes about the food, especially on the rather cruel methods of cooking turtles. I enjoyed his many encounters with fields of cabbages, something I too recall from bus rides in China. The first thing he does on his tour is to visit the Zhoukoudian site to see the fossilized remains of the Peking Man – who many believe to be the first ‘Chinese Man’. Is this a tourist activity that should regain popularity in Beijing? One can’t argue with Malaparte’s tour schedule, he takes in many cities and surely his talk of low prices and plentiful goods is not all false. Some of his interactions with locals are well written up, such as when a little girl playing in the mud in Xian gives him a pepple. Malaparte sees the gift as precious because the landscape for miles around is off clay with no rocks or pebbles (and there is the inference for me that he is conscious of the scarcity in the child’s life). American film director Walter Murch translated this anecdote into a poem called ‘Xian of Eight Rivers’ which I recommend. However, my overall feeling is that this is a book about what Malaparte wanted to find in China rather than what he actually did find. As for his meeting with Mao, I’m curious to know what the Great Helmsman thought of the Italian intellectual. I suspect he didn’t give him much thought at all but it’s something we’ll never know. The legend is that a Catholic priest and the leader of the Italian Communist Party visited Malaparte on his deathbed in Rome – and that both claimed he converted to their respective faiths.

1. ‘Io, in Russia e in Cina’ (Me, in Russia and in China) by Curzio Malaparte. I made English translations using Sousa Victorino’s Portuguese version ‘Eu, na Rússia e na China’, Circulo de Leitores, 1976. I read Portuguese pretty well. This book has only been translated into French, which I can’t read, and Portuguese. And, as I’m sure you now realise, I don’t read Italian.

2. ‘Kaputt’, by Curzio Malaparte, translated from the Italian by Cesare Foligno, Picador Classics, 1989, pg 147.

A shorter version of this appeared in 2018 in the LA Review of Books, China Channel, under the title ‘When Malaparte met Mao’. Sadly that site is now defunct.