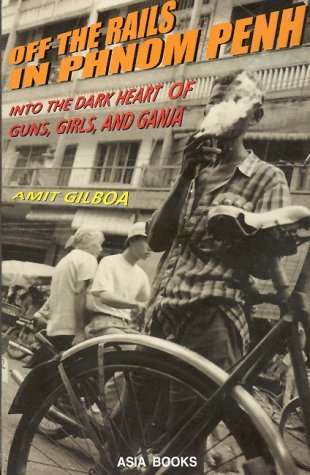

Earlier in 2023, I wrote a review based on what I remembered from having read “Off the Rails in Phnom Penh: Into the Dark Heart of Guns, Girls, and Ganja” in 2003. This book had popped into my mind many times over the years, and with a first-ever trip to Cambodia coming up, I thought I’d review it. Now that I’ve spent a week in Cambodia, and been lucky enough to find a copy of Off the Rails in a second-hand bookshop in New Zealand, I want to re-review it.

Off the Rails in Phnom Penh is a much better book than I remembered. It’s engaging and informative, and the editing isn’t bad, despite some reviewers getting a bee in their bonnet about ColUmbia instead of ColOmbia. What I remembered most was the chapter titled ‘Sex.’ This chapter details the adventures of a group of (mainly) English teachers who live or hang out at the Majestic Hotel. They make trips to brothel villages around Phnom Penh to sleep with teenage prostitutes for as little as two dollars.

Prostitution, which is usually considered morally wrong, exploitative, or at least shameful to partake of in the West, is more or less celebrated at the Majestic.

Not surprisingly, this section garnered the most attention and furore – how could people resist the outrage of these white male villains served to them on a plate? While the chapter remains an interesting exposition on a taboo topic, Off the Rails has much more going on. However, apart from an excellent piece in the defunct Mekong.net, I haven’t read any reviews commenting on author Amit Gilboa’s succinct summing up of Cambodia’s troubled history or his eyewitness account of the 1997 coup. Sex rather than violence outrages the Western mind. When reflecting on my trip, I found his chapter on Cambodia in the second half of the twentieth century helpful. It’s easy to keep in mind the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 79. What’s harder to remember is what happened from 1970 to 75, and from 1979 to 97. Gilboa explains both of these periods in a concise fashion.

The thing that disturbed me most during my second reading was that Hun Sen, who careful readers will note is the real villain of the tale, is still, in 2023, Prime Minister of Cambodia. Throughout the book, which came out twenty-five years ago, Hun Sen and his CPP (Cambodian People’s Party) are presented as ruthless operators who don’t hesitate to take violent action. When Hun Sen’s rival plan to meet, this happens:

“Hun Sen predicted – he didn’t threaten, he just predicted – there might be a grenade attack on the meeting. He wouldn’t have anything to do with it, of course, he just had an inkling it would happen.”

Another Hun Sen tactic is to accuse his enemies of what he himself is doing, as we find out during the coup Hun Sen launches against his co-Prime Minister, Prince Ranaridh.

Listening to Hun Sen angrily rail away, Reiner translates what he can. “He keeps talking about illegal weapons and the Khmer Rouge troops brought to Phnom Penh by Ranaridh. He says it’s not a coup but he has the force to prevent a coup by Ranaridh using the illegal weapons and KR troops.

“Classic CPP,” says Joe. “They do something and then accuse the other side of it.”

Joe and Reiner are but two of the many contacts Gilboa makes at the Majestic. They fit into Gilboa’s adventurer category of flotsam expats. The adventurers dabble in the girls, guns, and ganja but they have skills to operate outside Cambodia, a place in the mid-90s where teaching four hours of English a day, sober or not, could earn you a living. In the lifer category – those who couldn’t face up to the real world outside – are Eric and especially Mike. At one stage Mike is too wasted to get up and go to work. Eric tries to help:

Eric continues heroically trying to save his friend from himself but finally gives up and goes to class, leaving Mike comatose on the couch. I was touched by the concern this militaristic, racist, homophobic, child molesting smack addict showed toward his friend.

Even the amoral Eric can see Cambodia would be better off without Hun Sen, and claims with his military training he could take Sen out if the CPP’s political enemies would give him a sniper rifle.

“If FUNCINPEC can give me one Schmit-Rubens and a hundred thousand dollars, I’ll guarantee within one month, Hun Sen goes down.”

In the lawless, corrupt Cambodia of the 90s where government workers earned sixteen dollars a month but drove 50,00-dollar cars, Hun Sen was already working on his cult of personality and positioning himself as a humanitarian.

For the past couple of weeks, Phnom Penh has been abuzz because an unknown organization awarded Hun Sen this prize for his efforts toward peace.

During my recent Southeast Asia trip, I saw a cult of personality in the propaganda for the sinister Thai King and for Uncle Ho in Vietnam. However, the current political leaders of Thailand and Vietnam kept a low profile. By contrast, in Cambodia, I saw hagiographic pictures of Hun Sen and his wife – almost as many as of the previous and current king. Here is an example from the lobby of my hotel. Both Hun Sen and his wife are wearing medals and, naturally, she sports a Red Cross badge. The following image shows the late King Sihanouk and King Norodom. (Photo taken the very moment the storm hit.)

The United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia didn’t do anything when Hun Sen refused to accept the election results in 1993. He lost the election but brokered a power-sharing deal. Also – on the topic of where moral outrage should be directed – the UNTAC police and troops arriving in the war-torn country led to a huge increase in prostitution and AIDS. The worst offenders were the Bulgarians, nicknamed the Vulgarians.

UNTAC personnel were given a hundred and forty-five dollars a day for living expenses – in a country where the average income is about one hundred and twenty a year.

The chapter on drugs is perhaps the least interesting in the book. Modern-day backpackers in Southeast Asia of the weed-smoking persuasion would laugh at the photo of Gilboa proudly holding a large bag of low-quality ganja that cost him two dollars. A joke when you consider what’s now legally available on the streets of Bangkok as you can see below.

More impactful are the photos of burned-out tanks Gilboa took during the 1997 coup.

On a motorbike, he sets out to report on the coup and finds the airport and its surrounds looted by Hun Sen’s victorious soldiers. At one stage, the motorbike won’t start and he comes uncomfortably close to Khmer Rouge troops recently out of the jungle and now on the side of the CPP.

“Unlike the teenage soldiers in town who are generally good-humored, these advancing troops get ready to kill at the slightest excuse. I get a very bad feeling.

I enjoyed his amateur conflict reporting and admired his desire to find out what was going on. While a quote on the cover describes the book as a Gonzo rant in the style of Hunter S. Thompson, I found the book more the descendant of Michael Herr’s “Dispatches” about the Vietnam War, rather than anything by the overrated Thompson. Like Herr, Gilboa uses a lot of quoted speech in his work and it’s up to the reader to decide what to believe. But we get a sense of time and place.

Leave the conflict reportage to the professionals you might say. But I have a decidedly jaded picture of war reporters working for the big networks. In the book “Syrian Dust,” Francesca Borri, another disciple of Michael Herr, tells of reporters with big budgets turning up to war-torn Aleppo and paying fixers so they can get shots of kid soldiers with Kalashnikov rifles smoking cigarettes. These kinds of staged images allow CNN’s Anderson Cooper to employ his best morally outraged expression. The ‘real’ freelance war reporters like Borri can’t make a living…even if they ask for seventy euros an article they will be undercut by other desperados. And living in a conflict zone is not cheap.

Gilboa attempts to explain what makes the Khmer people tick. He doesn’t go particularly in-depth, but he’s more interesting than your friends telling you they too have been to Cambodia too, and the people were lovely, the food delicious, and the history sad. The author is a rare creature: a reflective extrovert. Despite real potential as a writer, he hasn’t added to this 1998 effort. Instead, he moved on to work as an actor in Chinese language soap operas – yes, as a token Mandarin-speaking white guy. And then reinvented himself as a percussionist in Singapore.

I can’t say I found Phnom Penh as charming as Gilboa did. One of the main changes since the 90s is the roads are now paved. The traffic remains chaotic. The lawlessness has gone but the city remains gritty. The only time I saw traffic cops was when they cleared the road to make way for a couple of black SUVs with tinted windows – something which hasn’t changed since the time of Off the Rails. Probably Sebastian Strangio’s “Hun Sen’s Cambodia” is a good book to read to know what’s going on. Hun Sen is now a big friend of China and if one wants to investigate vice in 2023, they need to look at Chinese organised crime in Sihanoukville.

I did come across three flotsam expats like those described in the book. My partner is Mexican and always keen to eat tacos. So we ended up in a foreign-run taco restaurant in downtown Phnom Penh. One of the owners sat at the bar smoking, cigarette ash falling down the front of his shirt. A big man, his tattooed forearms looked like those of a T-Rex against his beer belly. Lifting the beer glass to his mouth was obviously the extent of his exercise routine. From California, he’d been in Cambodia for twenty years. He used to be an artist, used to speak Spanish, used to study Khmer but had given up. A cartoon of him, his Cambodian wife, and his son on the wall showed he wasn’t completely full of shit about being an artist. He did a shot of tequila and began to tell of the good old days of dirt roads in Phnom Penh when a Khmer too high to hold a gun straight might try to rob you. He had a sadness about him, an air of opportunities lost. I didn’t think him a bad soul and he knew a few things about making tacos. His business partner, a Brit who took the orders, and ordered the Cambodian barman around was drunk and unpleasant, as was his Italian wife. Glassy-eyed and covered in tattoos, she loudly told the story of how she’d broken her leg while falling down the steps drunk. Very funny she thought it. The Californian too had a gammy leg, his ankle was swollen and bruised. A drunken accident? Gout? They talked about booze a lot – I used to find these Off the Rails expats fascinating in my twenties. Now they bore me. Probably the middle-aged Gilboa feels the same.

Review before my trip to Cambodia and re-reading the book

Off the Rails in Phnom Penh chronicles the adventures of the expat community in the 90s, in the post-civil war era of anything-goes hedonism. It made quite an impression on me and here I am writing a review twenty years after reading it… Cambodia has come a long way in the 21st century, and I don’t expect much of the vibe described in the book to remain. Be forewarned this review doesn’t strictly stick to the book.

Having seen what could happen in Thailand out alone at night with too many beers inside, I decided to skip Cambodia in my Indochina travels in 2003. I’d heard of the debaucheries on offer there and they scared me. Now, in 2023, I’m excited to finally visit that country this June.

Instead of Cambodia, I went to Laos to get away from – the unhealthy for me at that stage – Thailand. I’m not against a party lifestyle or P4P sex, but you’ve got to know how to lead this lifestyle so it squares with your moral limits, and you keep safe and healthy. Hang on, is that possible? Maybe not, and that’s part of the attraction.

In the Northernmost province of Laos, Phongsali, I did a three-day trek staying in Akha and Hmong villages. Although I saw Akha smoking opium, they didn’t offer me any.

Their teeth stained by blood-coloured juice freaked me out. I didn’t know chewing betels nut with slaked lime caused this. After, I went down to Laos’s temple town Luang Prabang and, in a hostel, swapped my copy of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American for Amit Gilboa’s Off the Rails in Phnom Penh.

I’ve talked to people who fired machine guns while drunk in Cambodia in the 90s and early 2000s and heard talk of shooting cows with bazookas. Some said they turned green and nearly passed out from ganja pizza (this you can still do I’m guessing). The guns and ganja are in Gilboa’s book, but where he aims to shock it with the underage prostitutes available for as little as two dollars. The book is set before the coup in 1997, a time of true off-the-rails hedonism. Hun Sen ousted his co-premier in this coup. Old Hun is still in charge! The resulting violence had a negative effect on the tourist industry and many expats left.

The expats Gilboa hangs out with at a hostel bar (if I remember rightly) are open about visiting prostitutes. Many of them are English teachers, a group whose reputation has taken many hits over the years. Gilboa only partakes in two brothel visits, on the first of which a girl of about 19 – who, interestingly, is Vietnamese – gives him a blowjob. Right there Gilboa has admitted something that would get him, by today’s standards, struck off the list of the human race in the West…with the liberal left being the first to yell for his lynching. I’m just old enough to remember a time in the 80s when the conservative right shouted the loudest to lynch moral transgressors. Gilboa claims he did it as research for his book. I think he was trying to find his own moral boundary. The second-century-AD-Gnostic Carpocrates believed people needed to go through every possible experience, both good and bad, to return to God. These days he looks to be a happy family man in Singapore. He hasn’t written another book. He’s probably scarred from the negative reaction to Off the Rails. Although he set out to cause a stir, he overestimated his ability to deal with the vitriol.

In much of Asia, prostitution is omnipresent, even if it’s illegal. As author Isham Cook has mentioned, it’s hard for the Western mind to comprehend the extensiveness of the industry in countries like Thailand and China. Here in NZ, it’s legal: our liberal leaders are enlightened…but nobody I know talks about it much. It still feels taboo. For a lot of Western men, their first encounter with a prostitute is in Asia, something they didn’t plan and wouldn’t have done in their own countries. That’s what they say anyway. I’m talking about backpackers or work visa holders rather than intentional sex tourists. Do they then regret it? Hard to say. Guilt around sex is in our programming, the original sin in the founding myth of our culture still holds a huge subconscious sway.

As an example of the prominence of red light activity in Asia, I’d like to discuss Wuhan. Yes, Coronavirusville itself. In 2003 and 2004, I was teaching English there. Compared to other places I’d lived in China – Dalian, Shanghai and Tianjin – Wuhan was a dump. I lived near downtown Hankou and in my city block or xiaoqu there were around twenty brothels, maybe more, I never counted them. Often brothels in China were disguised as hairdressers, but these places were just pink-lit and had women sitting around in relatively sexy clothing – nothing too racy. They weren’t brothels as you imagine, but, mostly, what one might describe as handjob parlours. A woman (or two) would lead the client to the second floor featuring a row of beds partitioned off from each other by flimsy plywood or a curtain, and then proceed to administer a rudimentary massage followed by a handjob. The usual Western reaction to this is disgust. But thinking about it – it seems like a safe outlet for male sexuality. These brothels were low class, above them existed a myriad of other options from KTV girls to kept mistresses. In China, there is a large population of floating migrant workers and expats (not all of whom are rich). These groups, if I were to hazard a guess, are 60 per cent male – or were so back then. What’s the best way for them to get their rocks off? Well, in any number of ways one might correctly answer or perhaps even better not at all. However, the handjob parlour seems a safeish option. One in which disease doesn’t spread (I’m not talking Covid). The women in the Wuhan parlours were usually in their early twenties and from the Hubei countryside and, on occasion, Wenzhou. The coastal city of Wenzhou south of Shanghai seems to provide an inordinately large percentage of China’s prostitutes. The handjob gig was a stepping stone to better things in the big city. Maybe twenty per cent of the girls were very attractive. This changed as China became richer and better opportunities came along. Often they had one day off every two weeks, but this was common practice in a lot of jobs at the time. The price in Wuhan was cheap and I can’t imagine these women earned much, but in Shanghai, this kind of job could be lucrative.

Back to Off the Rails. The book is not available digitally but a Spanish translation was put out in 2015 and I wrote to the publishers to see if I could get my hands on a PDF. Since Gilboa has moved on from writing, I thought I’d give the translator some press. My idea was to reread the book before reviewing it. The publishers have not responded as of yet. I didn’t reread the book before writing this review. A crime for which I tongue and cheek apologise.

If you are interested in more lurid tales from the same period in Cambodia, you may like William Vollmann’s “Butterfly Stories.” It’s one of his early works and his chronicling of prostitutes and Western men in Cambodia, unlike in the case of Gilboa, didn’t lead to any vitriol being aimed at him – to my knowledge anyway. This is (autobiographical) fiction, however, and Vollmann is an artiste, a literary darling.

Butterfly Stories is set in the early 90s, a couple of years earlier than Off the Rails, when the Khmer Rouge was still causing trouble.

View all my reviews